It may sound like a nit-picking detail: Where and how do you account for “reserves for replacement” when you try to value – and evaluate – a potential income-property investment? Isn’t this something your accountant sorts out when it’s time to do your tax return? Not really, and how you choose to handle it may have a meaningful impact on your investment decision-making process.

What are “Reserves for Replacement?”

Nothing lasts forever. While that observation may seem to be better suited to a discourse in philosophy, it also has practical application in regard to your property. Think HVAC system, roof, paving, elevator, etc. The question is simply when, not if, these and similar items will wear out.

A prudent investor may wish to put money away for the eventual rainy day (again, the roof comes to mind) when he or she will have to incur a significant capital expense. That investor may plan to move a certain amount of the property’s cash flow into a reserve account each year. Also, a lender may require the buyer of a property to fund a reserve account at the time of acquisition, particularly if there is an obvious need for capital improvements in the near future.

Such an account may go by a variety of names, the most common being “reserves for replacement,” “funded reserves,” or “capex (i.e., capital expenditures) reserves.”

Where do “Reserves for Replacement” Fit into Your Property Analysis?

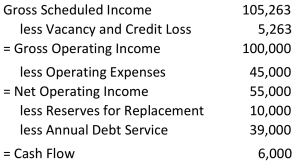

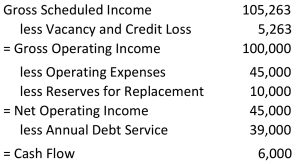

This apparently simple concept gets tricky when we raise the question, “Where do we put these reserves in our property’s financial analysis?” More specifically, should these reserves be a part of the Net Operating Income calculation, or do they belong below the NOI line? Let’s take a look at examples of these two scenarios.

Now let’s move the reserves above the NOI line.

The math here is pretty basic. Clearly, the NOI is lower in the second case because we are subtracting an extra item. Notice that the cash flow stays the same because the reserves are above the cash flow line in both cases.

Which Approach is Correct?

There is, for want of a better term, a standard approach to the handling capital reserves, although it may not be the preferred choice in every situation.

That approach, which you will find in most real estate finance texts (including mine), in the CCIM courses on commercial real estate, and in our Real Estate Investment Analysis software, is to put the reserves below the NOI – in other words, not to treat reserves as having any effect on the Net Operating Income.

This makes sense, I believe, for a number of reasons. First, NOI by definition is equal to revenue minus operating expenses, and it would be a stretch to classify reserves as an operating expense. Operating expenses are costs incurred in the day-to-day operation of a property, costs such as property taxes, insurance, and maintenance. Reserves don’t fit that description, and in fact would not be treated as a deductible expense on your taxes.

Perhaps even more telling is the fact that we expect the money spent on an expense to leave our possession and be delivered to a third party who is providing some product or service. Funds placed in reserve are not money spent, but rather funds taken out of one pocket and put into another. It is still our money, unspent.

What Difference Does It Make?

Why do we care about the NOI at all? One reason is that it is common to apply a capitalization rate to the NOI in order to estimate the property’s value at a given point in time. The formula is familiar to most investors:

Value = Net Operating Income / Cap Rate

Let’s assume that we’re going to use a 7% market capitalization rate and apply it to the NOI. If reserves are below the NOI line, as in the first example above, then this is what we get:

Value = 55,000 / 0.07

Value = 785,712

Now let’s move the reserves above the NOI line, as in the second example.

Value = 45,000 / 0.07

Value = 642,855

With this presumably non-standard approach, we have a lower NOI, and when we capitalize it at the same 7% our estimate of value drops to $642,855. Changing how we account for these reserves has reduced our estimate of value by a significant amount, $142,857.

Is Correct Always Right?

I invite you now to go out and get an appraisal on a piece of commercial property. Examine it, and there is a very good chance you will find the property’s NOI has been reduced by a reserves-for-replacement allowance. Haven’t these people read my books?

The reality, of course, is that diminishing the NOI by an allowance for reserves is a more conservative approach to valuation. Given the financial meltdown of 2008 and its connection to real estate lending, it is not at all surprising that lenders and appraisers prefer an abundance of caution. Constraining the NOI not only has the potential to reduce valuation, but also makes it more difficult to satisfy a lender’s required Debt Coverage Ratio. Recall the formula:

Debt Coverage Ratio = Net Operating Income / Annual Debt Service

In the first case, with a NOI of $55,000, the DCR would equal 1.41. In the second, it would equal 1.15. If the lender required a DCR no less than 1.25 (a fairly common benchmark), the property would qualify in the first case, but not in the second.

It is worth keeping in mind that the estimate of value that is achieved by capitalizing the NOI depends, of course, on the cap rate that is used. Typically it is the so-called “market cap rate,” i.e., the rate at which similar properties in the same market have sold. It is essential to know the source of this cap rate data. Has it been based on NOIs that incorporate an allowance for reserves, or on the more standard approach, where the NOI is independent of reserves?

Obviously, there has to be consistency. If one chooses to reduce the NOI by the reserves, then one must use a market cap rate that is based on that same approach. If the source of market cap rate data is the community of brokers handling commercial transactions, then the odds are strong that the NOI used to build that market data did not incorporate reserves. It is likely that the brokers were trained to put reserves below the NOI line; in addition, they would have little incentive to look for ways to diminish the NOI and hence the estimate of market value.

The Bottom Line – One Investor’s Opinion

What I have described as the standard approach – where reserves are not a part of NOI – has stood for a very long time, and I would be loath to discard it. Doing so would seem to unravel the basic concept that Net Operating Income equals revenue net of operating expenses. It would also leave unanswered the question of what happens to the money placed in reserves. If it wasn’t spent then it still belongs to us, so how do we account for it?

At the same time, it would be foolish to ignore the reality that capital expenditures are likely to occur in the future, whether for improvements, replacement of equipment, or leasing costs.

For investors, perhaps the resolution is to recognize that, unlike an appraiser, we are not strictly concerned with nailing down a market valuation at a single point in time. Our interests extend beyond the closing and so perhaps we should broaden our field of vision. We should be more focused on the long term, the entire expected holding period of our investment – how will it perform, and does the price we pay justify the overall return we achieve?

Rather than a simple cap rate calculation, we may be better served by a Discounted Cash Flow analysis, where we can view that longer term, taking into account our financing costs, our funding of reserves, our utilization of those funds when needed, and the eventual recovery of unused reserves upon sale of the property.

In short, as investors, we may want not just to ask, “What is the market value today, based on capitalized NOI?” but rather, “What price makes sense in order to achieve the kind of return over time that we’re seeking?”

How do you treat reserves when you evaluate an income-property investment?

The information presented in this article represents the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of RealData® Inc. The material contained in articles that appear on realdata.com is not intended to provide legal, tax or other professional advice or to substitute for proper professional advice and/or due diligence. We urge you to consult an attorney, CPA or other appropriate professional before taking any action in regard to matters discussed in any article or posting. The posting of any article and of any link back to the author and/or the author’s company does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation of the author’s products or services.

Mastering Real Estate Investing

Learn how real estate developers and rehabbers evaluate potential projects. Real estate expert Frank Gallinelli — Ivy-League professor, best-selling author, and founder of RealData Software — teaches in-depth video courses, where you’ll develop the skills and confidence to evaluate investment property opportunities for maximum profit.