In Part 2 of our discussion of real estate expense recoveries, we looked at several different methods that property owners use to recover some of their operating costs from tenants:

Simple pass-throughs — These typically work well in single-tenant properties, or in properties with no common area. The expenses chosen for reimbursement are billed to the single tenant; or if there are multiple tenants, then the charge is divided according to each tenant’s share of the total space.

Expense-stop pass-throughs — Some pass-through arrangements require the tenants to pay a just portion of the recoverable expenses. The landlord pays up to a certain amount, called an “expense stop,” and the rest is passed through to the tenants. The “stop” can be a dollar amount defined in the lease, or it can be a “base-year stop,” where the landlord pays whatever amount comes due in the first year of the lease and the tenants pay any increase in subsequent years.

CAM — In larger properties, where there is common space for the benefit of all tenants as well as for the public, the landlord my collect CAM (Common Area Maintenance) charges—expenses related to the maintenance of these common areas.

We left off at sticking point, however, regarding larger properties. If there is a significant amount common area, then the landlord will surely be thinking about the fact that this space accrues to the benefit of the tenants but doesn’t earn anything for the landlord. There must be a way to remedy this apparent inequity.

The Load Factor

Enter the “load factor.”

Recall two definitions near the end of the previous article:

usable square feet (usf): The amount of space physically occupied by a tenant.

rentable square feet (rsf): The amount of space on which the tenant pays rent.

The load factor represents a percentage of the common area, which is then added onto a tenant’s usable square footage to determine the tenant’s rentable square footage.

Let’s say a shopping center has a total area of 100,000 square feet. 90,000 is the usable area, occupied by tenants, and 10,000 is common area.

Load Factor = total area / usable area

Load Factor = 100,000 / 90,000

Load Factor = 1.11

What this means is that each tenant’s usable square footage will be multiplied by 1.11—in other words, bumped up by 11%—to determine its rentable square footage, the amount on which it pays rent.

Say for example that you operate a 2,000 square foot boutique in this 100,000 center, and have contracted to pay $40 per rentable square foot.

2,000 usable sf x 1.11 load factor = 2,220 rentable sf

2,220 rsf x $40 = $88,800 per year rent

Unlike what you did in the earlier pass-through models, you’re not paying an additional charge on top of your base rent here. Your base rental rate remains the same, but now it is applied to a greater number of square feet—the space you actually occupy plus a proportional share of the common area. This combination of your private space plus a pro-rata portion of the common space is what we now call your rentable square feet.

You and the other tenants are paying rent for your proportional shares of the common area from which you all benefit, and the landlord is receiving rent for all the space in the property. Cosmic equilibrium is restored.

Is It More Income or Less Expense?

Regardless of the name we give it—reimbursement, recovery, or pass-through—the end result is the same. The bottom line of our Annual Property Operating Data (APOD) form, Net Operating Income, is increased. The final issue to confront is how do we account for this additional money when we assemble a presentation or analysis?

One way that I see often, and which I believe to be incorrect, is to treat the reimbursement as if it were a negative expense—in other words, to show the expense reduced by the amount reimbursed. For example, if the actual property tax bill were $10,000 and the amount reimbursed were $9,000, then by this method the property tax expense would be shown as $1,000. Why do I say this is incorrect?

The purpose of an APOD, or of any income-and-expense statement, is to convey information that is both accurate and useful. The taxes for this property are $10,000. If you were a broker or property owner and handed me a report that showed taxes of $1,000, I would…

a) suspect you were trying to con me

b) doubt all of the rest of the numbers on your report

c) be denied essential information I need to evaluate the property (e.g., the true cost of property taxes and the lease terms regarding expense reimbursement)

d) find another broker or owner to work with

e) all of the above

The correct answer, of course, is “e.” You’ve missed a key ingredient of successful business discourse: clarity. You should convey your analysis of a property in terms that are unambiguous, accurate, and relevant to your audience.

If you don’t treat the reimbursement as a negative expense, then how should you handle it?

You should treat it as revenue, the same as rent.

It is rent. The amount may be based on a calculation involving one or more operating expenses, but it is still money paid by a tenant to a landlord under a lease agreement. If it walks like a duck, etc. Many lease agreements will in fact describe the reimbursement as additional rent.

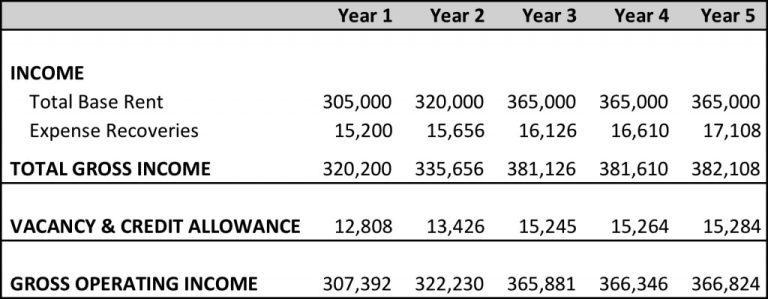

You can then apply a vacancy allowance to the total of base rent plus recoveries to account for the loss of both from a vacant unit. The top portion of your APOD might look like this:

(One side note on the interplay of vacancy on expense recoveries: Some leases will contain a gross-up clause. In such a lease, if there is less than full occupancy (which is defined in the lease, and is often pegged at 90 or 95%), then the landlord may take certain variable expenses that would be directly affected by the level of occupancy, such as janitorial cost, and “gross them up” to the amount they would be at full occupancy.)

In these three articles I’ve given you the abridged version of simple, single-tenant pass-throughs; pro-rated multi-tenant pass-throughs; expense stops; base-year stops; CAM charges; load factors; and even presentation issues. But there is no limit to the creativity of landlords and tenants in their pursuit of successful dealmaking. If you’ve been part of novel expense-recovery design, please share it with us.

The information presented in this article represents the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of RealData® Inc. The material contained in articles that appear on realdata.com is not intended to provide legal, tax or other professional advice or to substitute for proper professional advice and/or due diligence. We urge you to consult an attorney, CPA or other appropriate professional before taking any action in regard to matters discussed in any article or posting. The posting of any article and of any link back to the author and/or the author’s company does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation of the author’s products or services.

Mastering Real Estate Investing

Learn how real estate developers and rehabbers evaluate potential projects. Real estate expert Frank Gallinelli — Ivy-League professor, best-selling author, and founder of RealData Software — teaches in-depth video courses, where you’ll develop the skills and confidence to evaluate investment property opportunities for maximum profit.