Q. Can you explain more about how preferred return works in a real estate partnership? Does it always have to go only to the limited partner or non-managing partner?

A. The first point to make about real estate partnerships – whether limited, general or LLC – is that there is certainly no single, pre-defined structure used by all investors. In fact, you may be hard pressed to find two partnership agreements whose provisions are exactly the same.

Not all partnerships include a preferred return but, in those that do, its purpose is to counterbalance the risk associated with investing capital in the deal. Typically, the investor is promised that he or she will get first crack at the partnership’s profit and receive at least a X% return, to the extent that the partnership generates enough cash to pay it. In most partnership structures, the cash flow is allocated first to return the invested capital to all partners. The preferred return is paid next, before the General Partner or Managing Member receives any profit.

There are some variations as to exactly how the preferred return might be set up. If the partnership does not earn enough in a given year to cover the preferred return, the typical arrangement is to carry the shortfall forward and pay it when cash becomes available. If necessary it is carried forward until the property is sold, at which time the partners receive their accumulated preferred return before the rest of the sale proceeds are divided. Again, that assumes that the sale proceeds are in fact sufficient to pay the preferred return. If not, the limited partners have to settle for whatever cash is available.

The return may also be compounded or non-compounded. In other words, if part or all of the amount due in a given year can’t be paid and has to be carried forward, the amount brought forward may or may not earn an additional return (similar to compound vs. simple interest). The usual method is for it to be non-compounded. Hence the unpaid amount carried forward does not earn an additional return, but remains a static amount until paid.

An alternative but less common approach is to wipe the slate clean each year. If there isn’t enough cash to pay the preferred return, then the partnership pays out whatever cash is available and starts over from zero next year.

Real estate partnerships will typically define percentage splits between General (i.e., managing) and Limited (i.e., non-managing) partners for profit and sales proceeds. These splits do not come into play until the obligation to pay the preferred return has been met.

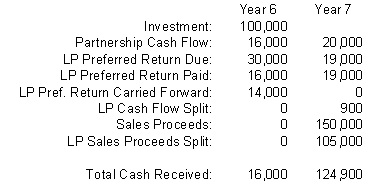

For example, let’s say that a limited partner invests $100,000. She is promised a 5% preferred return (non-compounded), 90% of cash flow after the return of capital and payment of preferred return, and 70% of sale proceeds. In the first five years, the partnership generates just enough cash to return the invested capital to all partners. Hence, all future cash flows represent profit. The partnership has a $16,000 cash flow the sixth year, a $20,000 cash flow the seventh year and also sells the property at the end of the seventh year with total proceeds of sale of $150,000. Here is what happens:

The Limited Partner should receive a preferred return of $5,000 per year (5% of her $100,000 investment). By the end of year 6 she hasn’t received any of this return so she is owed $30,000. In the sixth year the partnership cash flow is only $16,000, so that is all she gets; the balance due is carried forward to year 7. In that year the partnership cash flow of $20,000 is sufficient to pay the $14,000 owed from year 6, the $5,000 from year 7 and still leave enough ($1,000) to split 90/10 with the General Partner. Finally, the property is sold at the end of year 7 with $150,000 proceeds to split 70/30 with the General Partner.

Regarding the question, “To whom does the preferred return go?” it is of course possible to structure a partnership so that it goes either to the General or the Limited partner or to Donald Duck if you think that’s a good plan. The presumed purpose of the preferred return is to encourage non-controlling investors to risk their capital in your project; and that encouragement often takes the form of a conditional promise of a minimum return, the “preferred return.” It seems to me that you would have a difficult time raising money from investors if your underlying message were, “This deal is so shaky that I need full control plus first dibs on the cash flow. If there’s anything left, you can have some.”

Run the numbers, but think beyond them. A good partnership is one where all the parties can enjoy a reasonable expectation of success.

The information presented in this article represents the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of RealData® Inc. The material contained in articles that appear on realdata.com is not intended to provide legal, tax or other professional advice or to substitute for proper professional advice and/or due diligence. We urge you to consult an attorney, CPA or other appropriate professional before taking any action in regard to matters discussed in any article or posting. The posting of any article and of any link back to the author and/or the author’s company does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation of the author’s products or services.

Mastering Real Estate Investing

Learn how real estate developers and rehabbers evaluate potential projects. Real estate expert Frank Gallinelli — Ivy-League professor, best-selling author, and founder of RealData Software — teaches in-depth video courses, where you’ll develop the skills and confidence to evaluate investment property opportunities for maximum profit.